Karl Edward Wagner Special Award Winner: Ray Harryhausen by Stephen Jones

Ray Harryhausen was born in Los Angeles on 29 June 1920. As a young boy, he was fascinated by dinosaurs and constantly urged his father to drive him across town to the famous La Brea Tar Pits in Hancock Park to see the trapped remains of prehistoric animals. He also frequented the Museum of Natural History near the University of Southern California, studying the reconstructed dinosaur skeletons.

In 1933, Harryhausen went to see King Kong with his mother at Grauman’s Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. “I didn’t know anything about the film,” he explained, “but I was enthralled. I’d seen guys in gorilla suits, but when I saw Kong I knew he hadn’t been done that way. I came out of the theatre stunned and haunted.”

The thirteen-year-old Harryhausen became fascinated with the film, returning time and again in an attempt to discover how the effects were achieved. A behind-the-scenes article in Look magazine gave him some of the information, plus the name of the man who had created the effects—fellow Californian Willis Harold O’Brien (“Obie” to his friends).

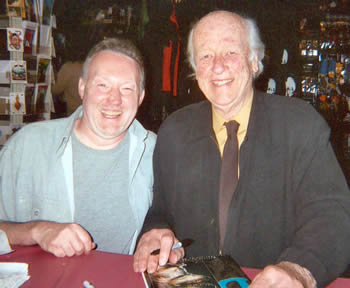

Signing at London’s National Film Theatre (1993)

The art of stop-motion animation had been around almost since the birth of cinema itself, but it was O’Brien who first saw the commercial possibilities of the technique.

A highly detailed and meticulous process, it involves the frame-by-frame manipulation of a physical object to make it appear to move on its own. This is achieved by moving a jointed or malleable figure very slightly, exposing a photographic frame, and then repeating the process twenty-four times to produce one second of film. When the many thousands of frames of a finished animation sequence are projected, the illusion is that the figure is animated in a fluid and continuous movement.

Around 1915, O’Brien began experimenting with filming a one minute test reel featuring a miniature dinosaur and a caveman constructed from modeling clay over crude wooden skeletons. After meeting nineteen-year-old Mexican sculptor Marcel Delgado, O’Brien was given the opportunity by First National Pictures to create the special effects for a $1 million adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s adventure novel The Lost World (1925). The film took two years to complete and during a ten-hour day, O’Brien’s intricate and time-consuming work would be lucky to result in thirty-five feet of film (or thirty seconds screen time).

Harryhausen’s own first attempts at stop-motion animation were accomplished with a 16mm camera borrowed from a friend. “I built a cave bear in miniature,” he recalled, “and covered the wooden frame with a hunk of fur from an old coat of my mother’s.” Winding back the film, he matted himself and his German shepherd named Kong into the sequence.

Although these early attempts were somewhat crude, he persevered and began to refine his filmmaking techniques.

When Harryhausen learned that O’Brien was working in Culver City on the eventually aborted War Eagles (1939) for M.G.M., he was confident enough to visit his idol in the company of his mother and father. As he recalled: “It was naturally a very big moment for me, as the admiration I had for the film King Kong and the work of Mr. O’Brien had already developed into almost a fetish. I remember he looked at my rather sausage-legged stegosaurus and said something that stood out in my mind for years. He said, ‘You’ve got to get more character into your animals’. It was then I decided to study sculpture, anatomy and art much more seriously.”

While Harryhausen developed his dream project, Evolution (1940)—”The film was to be an entire history of this planet,” he recalled. “Naturally I started with the dinosaurs, because that’s what interested me the most”—he soon found himself working on George Pal’s animated Puppetoon shorts for Paramount Pictures.

Following his wartime experience with Frank Capra’s military film unit, in 1945 Harryhausen created a series of animated fairy tales. The result was an eleven-minute short entitled The Storybook Review (aka Mother Goose Stories), released to educational outlets the following year.

He continued the series with The Story of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ (1949), The Story of ‘Rapunzel’ (1951), The Story of ‘Hansel and Gretel’ (1951) and The Story of King Midas (1953).

Many years later, a final fairy tale, The Story of ‘The Tortoise and the Hare’ (2002), which Harryhausen had started and abandoned in the early 1950s, was completed by a team of young animators.

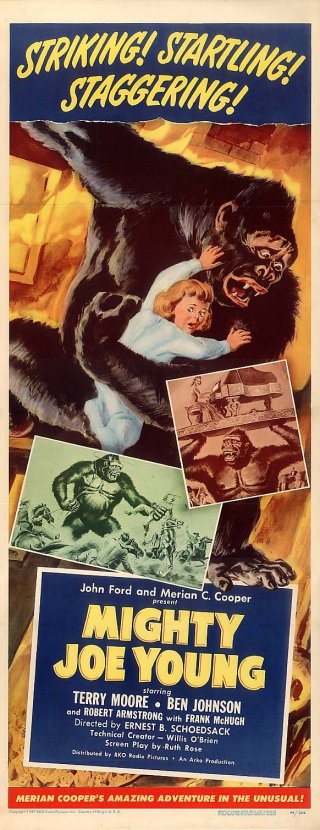

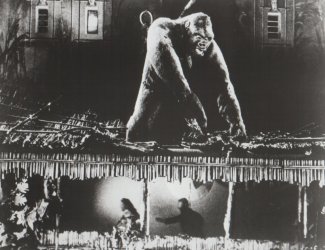

In 1947, Merian C. Cooper teamed up with John Ford to produce a variation on King Kong. He reassembled many of the same team, including O’Brien, who in turn hired the twenty-eight-year-old Harryhausen as his assistant. The effects for Mighty Joe Young (1949) took O’Brien and his crew of twenty-five over a year to complete and, as Harryhausen revealed, “I did about eighty-five per cent of the animation. Most of Obie’s time was, by necessity, consumed in planning and devising ways of doing the many complicated shots.”

Although the film was not a huge box-office hit, O’Brien received the 1950 Oscar for his contribution, after being shamefully overlooked for King Kong.

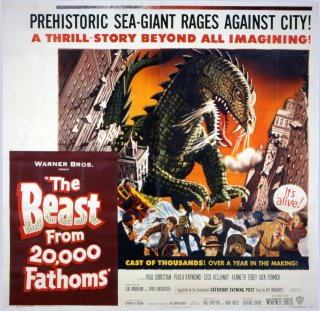

In 1953, Harryhausen landed his first solo feature assignment when he was paid just $10,000 to create the stop-motion effects for The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), based on a Saturday Evening Post story by Ray Bradbury. Using a split-screen process, he developed a method of inserting his articulated three-dimensional model between the live action background and foreground without resorting to expensive miniatures or glass paintings. The film was a hit, and the young animator’s career assured.

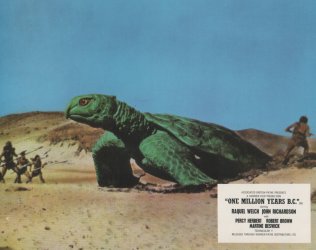

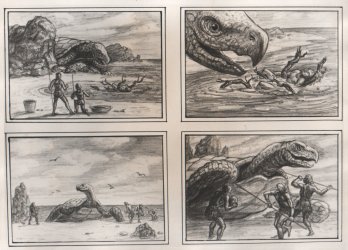

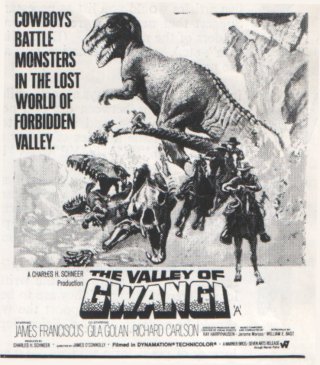

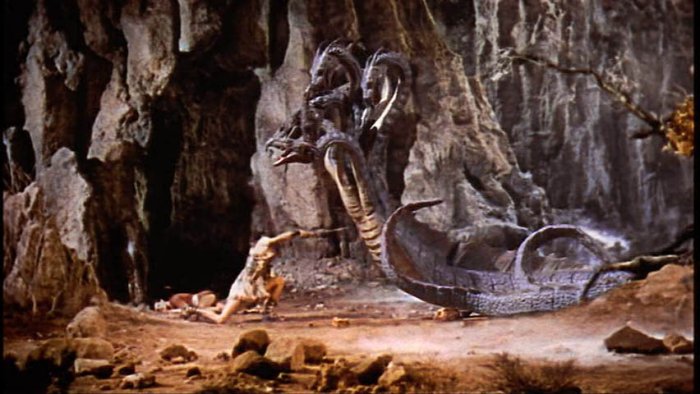

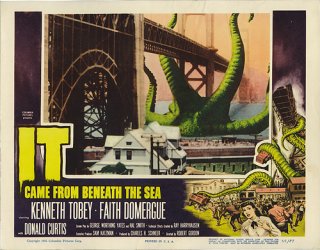

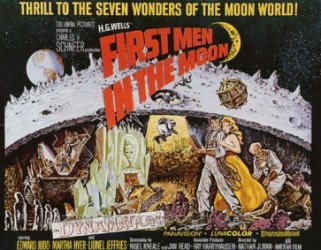

Although Harryhausen had originally met Charles H. Schneer in the Army during World War II, they began their long association in 1955 when Schneer produced It Came from Beneath the Sea. They followed this successful collaboration with Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956), 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957), The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960), Mysterious Island (1961), Jason and the Argonauts (1963), First Men in the Moon (1964), The Valley of Gwangi (1969), The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973), Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) and Clash of the Titans (1981). During this period, Harryhausen worked with other producers only twice—on the documentary The Animal World (1955) with Willis O’Brien for Irwin Allen, and Hammer Films’ One Million Years B.C. (1966) starring a memorable Raquel Welch in designer furs.

For The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Harryhausen introduced a new process which he dubbed ‘Dynamation’. Schneer described it as “a photographic process which combines a live background, in colour, with a three-dimensional animated figure in combination with flesh and bone actors.”

However, Harryhausen’s success and reputation over the years have not just rested on his technical accomplishments; he learned his lesson from O’Brien well, as he explained: “Most of our dinosaurs are very accurate from the physical point of view. Visually, though, I feel it is far more important to create a dramatic illusion than to be bogged down with detailed accuracy.”

Four years after his last film, Clash of the Titans, Harryhausen revealed to an audience at the San Jose Film Festival that he would not be involved in Force of the Trojans, the next project by his longtime collaborator Charles H. Schneer, on which he was to have worked with George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic. Instead, he was retiring.

“When we started out in the 1950s, we were the only ones doing fantasy,” said Harryhausen. “We like to think we kept it alive. Now there are so many companies, everything’s been done.

“There reaches a point where you can’t see yourself spending another year of your life in a darkened room twisting little models around. But I still love the work and I miss it sometimes.

“I’ve been spending my time doing the things I’ve really wanted to do for a long while, but never had the time for. I’ve been making bronze figures from some of the characters we used in our films. When you devote too much time to a film, you have very little time to see your family. Now I’m spending a lot of time getting reacquainted with them.”

As it turned out, Force of the Trojans was never made. Nor was the proposed Sinbad on Mars. Instead, Harryhausen has lent his name to a range of model figures, comic books, limited edition prints and DVD releases. Meanwhile, along with his wife Diana, he continues to split his time between London, Spain and his hometown of Los Angeles where, whenever he has the opportunity, he still sees his old childhood friends, Ray Bradbury and Forrest J Ackerman.

Ray Harryhausen continues to exert an enormous influence on contemporary filmmakers: he made cameo appearances in Spies Like Us (1985), Beverly Hills Cop III (1994) and the 1998 remake of Mighty Joe Young, as well as voicing the Polar Bear Cub in Elf (2003). The restaurant in Disney/Pixar’s Monsters, Inc. (2001) is named after him, while a grand piano in Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride (2005) carries a gold plate with his name on it.

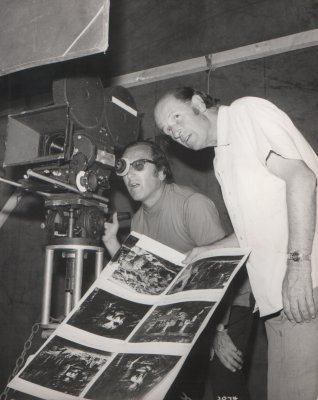

during the shooting of The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973)

Although The 8th Voyage of Sinbad starring Keanu Reeves was cancelled by Columbia Pictures in 2005, a remake of Clash of the Titans has been announced by Warner Bros., and Willis O’Brien’s War Eagles project has recently been resurrected with Harryhausen as one of the producers.

“I’m very happy that so many young fans have told me that my films have changed their lives,” he revealed. “That’s a great compliment. It means I did more than just make entertaining films. I actually touched people’s lives—and, I hope, changed them for the better.”

Harryhausen has admitted that he was a little disappointed that his many films were passed over for Oscar consideration in their time. However, in 1992 he was finally awarded a long-overdue honorary Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement, “I was delighted to be recognised,” he said, “and pleased now that animation is recognised as a legitimate profession.”

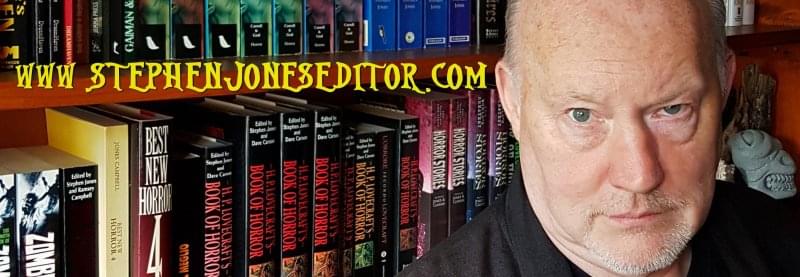

Although I had been a fan of his films since the mid-1960s, my first meeting with Ray Harryhausen was at an event organised by London’s Gothique Film Society in April 1971. (For those who may be interested in such things, there are photos of my eighteen-year-old self inspecting the original models from Jason and the Argonauts in the third and final issue [Summer, 1972] of the American fanzine Special Visual Effects Created by Ray Harryhausen, or FXRH for short.)

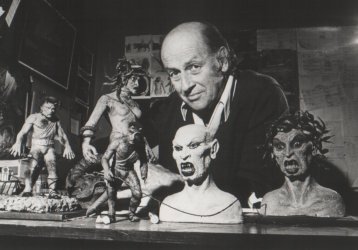

Although we met up again at various events over the years—including a BFS Open Night in Holborn that I helped organise, the 1987 World Science Fiction Convention in Brighton, and the Famous Monsters of Filmland convention in Los Angeles—it was not until 1993 that I had the pleasure of getting to know him personally, after he kindly contributed the Introduction to my book The Illustrated Dinosaur Movie Guide. Not only was I invited to his London home to view his remarkable stop-motion models and bronze sculptures, but we also undertook a brief signing tour together to promote my volume and the reissue of his Ray Harryhausen Film Fantasy Scrapbook from Titan Books.

So let us all raise a glass at the Awards Banquet and celebrate the career of a man who, for more than three decades, spent his life realising the worlds of gods and monsters through the magic of stop-motion animation.

Congratulations, Ray!

—Stephen Jones

London, August 2008

Copyright © 1993, 2008 by Stephen Jones.

Parts of this article were originally published in The Illustrated Dinosaur Movie Guide (Titan Books, 1993). All rights reserved.